Rebecca Morgan “Self-Portrait Wearing Hat” (2012, graphite and oil on panel, 24” x 21”)

Keith Schweitzer of ART(inter) in conversation with artist Rebecca Morgan.

KS: I’d like to talk at length about your ceramic works. I’ve watched them develop over the years, and they’ve become increasingly interesting. But first let’s discuss your drawings, as they seem to be the very essence of all of your work. Would you say that is a fair statement?

RM: I feel that I identify most with drawing, and that it is absolutely the basis for all my work. It is an almost intangible, utter attraction. I love that you can get such variety and character out of line quality; you can say a lot with just a few hatches or economical decisions. My large, life-size graphite drawings suggest a tone and mood that I wouldn’t necessarily be able to convey in a painting. I draw every day, whether it is a drawing with ink or a drawing with a stylus on my phone; all of the work that I do finds its source in drawing. My phone also serves as a sketchbook: I make small cartoons and post them on Instagram. Cartooning is a break from the formal thoroughness that the large graphite drawings and the substantial paintings demand.

Rebecca Morgan “Odalisque” (2014, graphite on paper, 65″ x 94″)

All my paintings are realized out of drawings. First I make an elaborate and thorough graphite underdrawing on a smooth gessoed wood panel. I then paint over the graphite, but in thin layers with glaze so that the drawing is still visible. Unless I build the paint up it’s rarely obliterated, so the viewer is able to see the drawing underneath the painting. I love to be able to see the drawing working in tandem with the paint, giving the subject dimension and volume in a direct way.

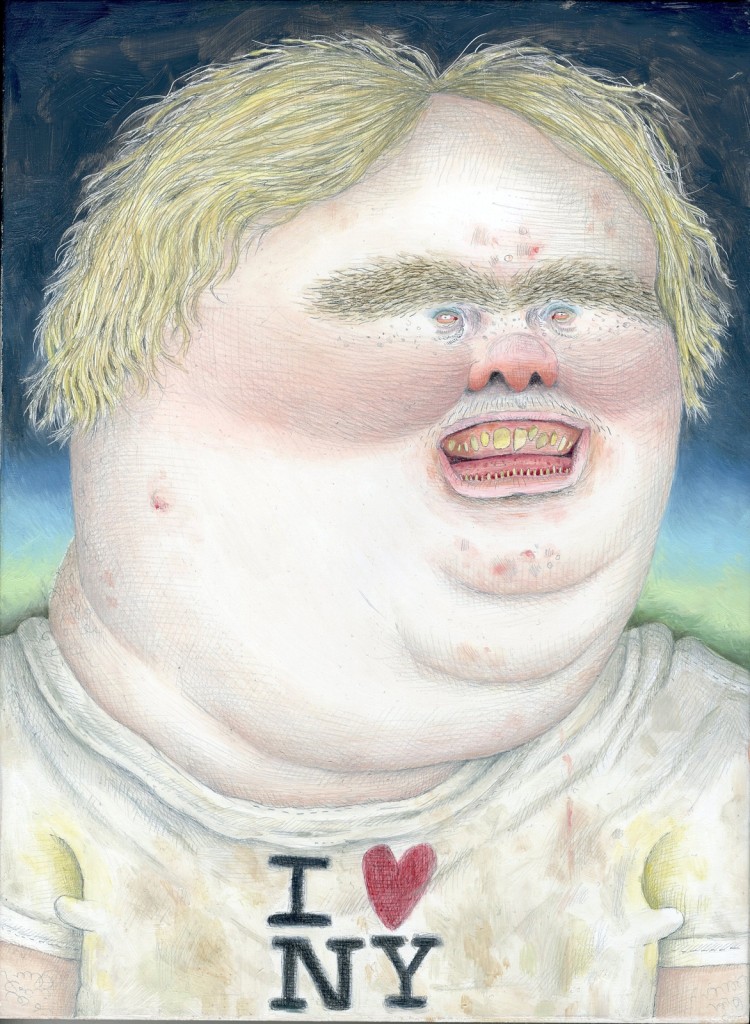

Rebecca Morgan “Tourist Bumpkin at Dusk” (2011, graphite and oil on panel, 12″ x 9″)

KS: If I were to describe your style of work, in words, to someone visually unfamiliar with it, I think they’d have a difficult time imagining how astonishingly successful the works actually are. There’s a heavy dose of cartooning, a pinch of Flemish Baroque, and a heaping spoonful of what I can only describe as Rebecca Morgan. How do you describe your work and what’s the secret recipe?

RM: There’s no secret recipe, but several themes define all of my work.

Comedy is very important to me. I’m obsessed with it in almost all its incarnations. I don’t have an agenda or formula for making something funny or whimsical; I mostly make humorous characters for my own relief. Real life is messy and abject. Real life isn’t usually slick, easy, or aesthetically beautiful, but comedy softens the blow. There are so many horrific things in the world that sometimes the only way I can cope with them is to make a funny cartoon.

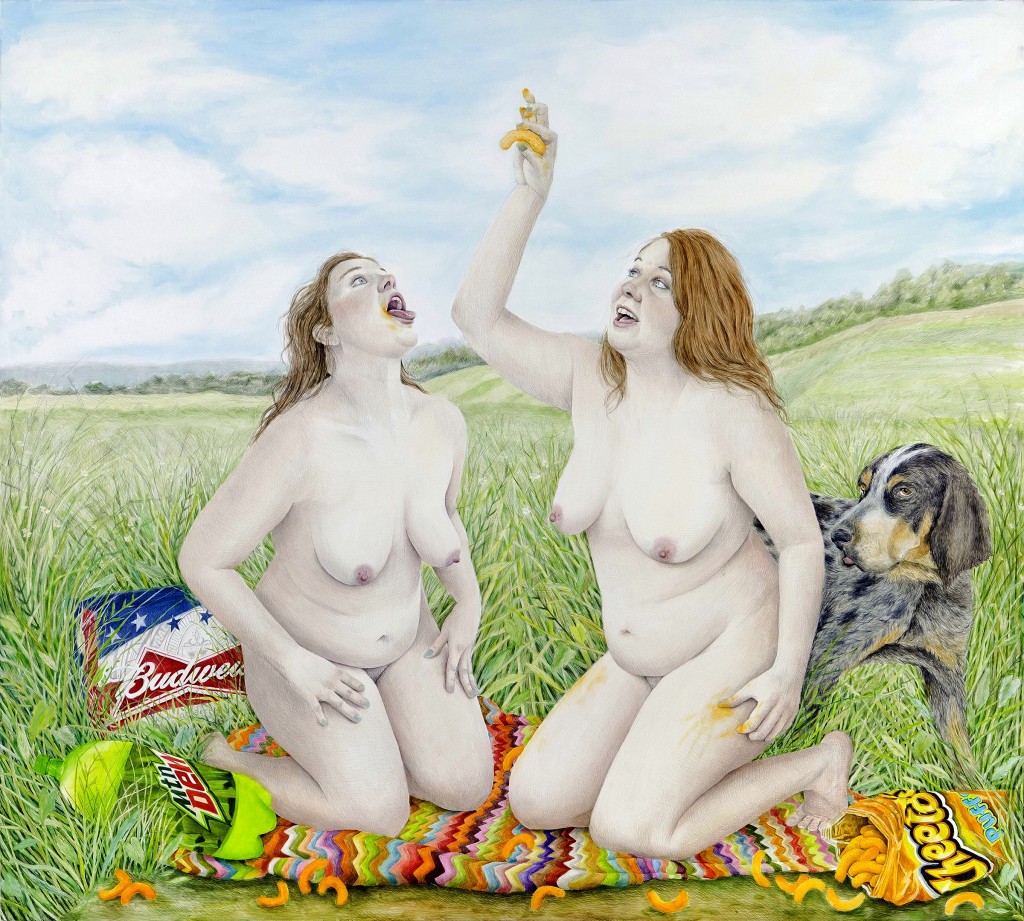

Growing up in rural Pennsylvania has always been the foundation of my aesthetic. I’ve always admired small town fun, traditions, and slowness, and I take pride in being a country girl. A lot of the images I make include props from my upbringing: hunting camps, blue ribbons from the fair, hunting dogs, the deep woods, the downed dead buck—the list of archetypes goes on. Aesthetically, for me, there wasn’t much not to love.

Rebecca Morgan “Homecoming Picnic” (2012, graphite and oil on panel, 62″ x 69″)

Though I take great pride in my roots and have reverence for the country that inspires me, in a lot of ways it’s constricting. Central Pennsylvania is very conservative, and its isolation made it pretty difficult to come across new things or pursue my wide-ranging interests. I always hoped I would get to live in New York, but when I finally attended graduate school at Pratt Institute I found myself situated liminally between the romanticism of the urban and the romanticism of the rural. I want my work to enact this dialectic between a defense and a critique of rural living, and everything that I make comes out of the bittersweet discomfort I feel as I navigate between these two zones.

I feel very close to the Old Masters, particularly Northern Renaissance and Flemish genre painters such as Frans Hals, Peter Rubens, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and Adrien Brouwer. I like how the artists of the Northern Renaissance celebrated aspects of everyday life, commemorating the bourgeoisie and honoring the gritty rural folk. They embody a sense of timelessness, weirdness, cheekiness and reverence for the common man that I hope to emulate in my own work. I am also very inspired by American folk art and outsider art, especially Pennsylvania Dutch crafts, historical ephemera, and early American ceramics. At the same time, cartooning and the grotesque have always been profoundly important to me. The ‘low art’ of MAD Magazine (artists like Al Jaffee, Harvey Kurtzman, Don Martin, and Jack Davis) was deeply influential to me at a very young age. I loved how they could present brutal satirical truth in a playful, sick, and elegant way. Robert Crumb might be one of the highest gods in my pantheon. I feel very close to Crumb in that he put his diaristic, self-loathing, perverted personal imagery to the fore, exploring carnal indulgence and detailing his highs and lows in lurid, intimate accounts. He is an incredible draftsman and makes great decisions; I love the way his vernacular imagery complements his formal execution. I am very attracted to both that Old Master touch and outsider sensibilities, and I have tried to nestle myself between them.

I want to communicate the rawness of our everyday lives – the tender and maybe grotesque moments of our private existence made public. I deeply value brutal truths and being genuine; I think there is a real freedom when you expose what’s not socially acceptable, owning and reclaiming it. I am interested in bad behavior and giving in to desire and Dionysian pursuits. I like the idea of my characters blissfully doing whatever they want—pleasure-seeking, wild men and women indulging in their every desire. Like my characters, I am a pleasure-seeker in all arenas. Food, relationships, humor, living a life of ease: these things may not be a reality all of the time, but I fantasize a life of unrelenting pleasure—a personal utopia!

KS: Your characters, the subjects in your works, are beautiful and bletcherous at the same time. There is something very honest and innocent about them, but they are far from virtuous. They seem blissfully naive and uninhibited. Who are they?

RM: There is the expression in art: ‘paint or make what you know’. I know myself very well—in fact, I am hyperaware. I use myself as a diaristic model; even when the cartoons or figures are not outrightly me, they represent a veiled self-portrait. As a tween I had huge bushy eyebrows and a faint mustache, so it’s like a little homage to the awkward shit that ultimately defined me. I think comedy works in that way, too: making fun of yourself and telling the world your own shortcomings before anyone else can get to you first. The more you embrace your own flaws, the less ammunition others have against you. Be it emotional discomfort, feeling trapped between the urban and the rural, self-loathing, indifference or confidence, romance and lack thereof, or living in my childhood home in my Pennsylvania hometown, illustrating intimate scenes and scenarios of my life lets me reclaim power and ownership of those hard times and weird emotions. Humor is cathartic for me. Embracing the discomfort, flaws and oddity is a way to turn it into lightness. I think most people can identify with that, and hopefully it makes other people relate and laugh at themselves (and me) through the work. I am endlessly fascinated by humans; the body is so potent as a vessel to convey all kinds of narratives. This is why I am a figurative artist.

Rebecca Morgan “Self Portrait Post MFA Wearing a Smock of a Former Employer” (2012, graphite and oil on panel)

The face jugs, cartoons and paintings represent a kind of blissful ignorance: they’re totally fine with looking so hideous and awful; it’s of no consequence to them. In my mind, that empowers them. Though covered in acne, wrinkles, and blemishes, their confidence and contentment is the ultimate acceptance of self-love. These characters are blissfully unaware, unruly, wild and untamed. They live off the grid and free, unaffected by anyone or anything’s influence, and I’m very attracted to that concept. I am always interested in the anti-hero, the underdog, the unlikely winner. I root for them and I see a lot of myself in them.

The art world can be a very serious place, and in that context sometimes it simply feels good to make a cartoon Mountain Man vomiting. To make others feel good is one of the greatest responses I could elicit from an audience, offering repose from all the nuttiness out there. As artists and as people, we’re constantly in a cerebral, overthinking froth, and very often I just really wish I could indulge in this stereotype of absence.

KS: Now back to your ceramic works, the jugs. The history behind this form of pottery, which are more formally known as Ugly Face Jugs, shows influences from differing European and American time periods, much like your own work overall. They’re mostly associated with the American South, having been introduced here by African slaves and later adopted as a Southern Folk Art. What first interested you in this form of pottery? When did you first start creating them?

RM: Growing up, face jugs were a common image and presence in museums, homes, and antique stores, especially in the South, where I have spent some time. Slaves used face jugs as grave markers designed to scare and keep the devil away. If they broke while exposed to the elements, it meant the soul was restless, or wrestling with the devil. I always knew face jugs as personally crafted vessels used to store liquor; their features would frighten children so they would not to try to meddle with the contents. I think of my work as an extension of the face jug tradition, expounding on a familiar ‘art’ object from the country as an homage in my own visual vocabulary.

Rebecca Morgan “Hot Lip Jug” (2014, terracotta, 5″ × 4″ × 4″)

As a child, I was not exposed to fine art. But all around me I saw hex signs, antiques, handcrafted tchotchkes, utilitarian objects, and all sorts of unique ephemera which informed the aesthetic I eventually developed. The jugs reclaim that vernacular. To that I added my own personal language of mark-making, evoking the style of my cartoons.

I really view these as treasured objects, magical and highly revered. I absolutely created them with the idea that they personified an intangible reverence for the pastoral. When I think of them animated, they are right at home with the country spells, secrets, history and traditional storytelling of Early American tales and Appalachian mysticism. Though an ambiguous narrative lurks behind them, I think they are fundamentally utilitarian objects for people. Yet they are autonomous creatures as well, as if they’ve always just been sitting in the woods existing on their own. In a lot of ways, I feel like they don’t belong to anybody. That is putting a lot of narrative weight on them, but they definitely come from some weird intense place and enact some sort of story.

Rebecca Morgan “Big Sweet Jug” (2014, terracotta, 14″ × 9″ × 10″)

KS: I’ve observed, with enthusiasm, a clear evolution in your ceramics over time. I imagine that it is a fun format to work with. The earliest works seemed looser than your recent pieces. I see more of your drawings in the newest jugs, as if your flat works have leapt out into the physical world. There is a tremendous amount of detail now, and it seems that you’ve truly found yourself in this medium. How has this progression felt? What do you have in store for us?

RM: One of the things I like most about the ceramic work I am doing is that it doesn’t have to be perfect. In fact, when it comes to my face jugs and sculptures, imperfections are welcome. Unlike my paintings or drawings, which often have to capture a specific mood or likeness, in this medium there is less pressure and need to be convincing. Over time, my jugs have become more detailed, reflecting the evolution of my cartoon style.

This summer was the first time I experimented with the firing process of raku, and it had a big impact on my work. Raku is a glazing process that leaves much of the results up to chance. The glazed piece is fired to 1800 degrees before being pulled out of the open kiln, exposed to oxygen, and immediately plunged into a metal bucket filled with newspaper or sawdust. The final piece will be metallic, rainbow, sfumato, matte or brilliantly glossy, depending on a multitude of factors including the glaze, technique, and how it reacted to the contents of the bucket. When I pulled out my first jugs it was an epiphany. Left to chance, there was so much individual variety in the surfaces. Raku is primordial; instead of choosing what color the jugs would be with commercial or studio glazes, for the most part the final result is entirely unto its own making. You can’t buy these surfaces in a bottle, and raku just felt so much more honest than using commercial glazes, closer to the heart of how I always envisioned the jugs. I have always created busts and figurines, and in the future I intend to concentrate more on non-jug sculptures. I also plan on highlighting the jugs as content in my two-dimensional works as well, creating new paintings and drawings that transform their meaning and context.

View more of Rebecca Morgan’s artwork on her website or on Instagram: @rebeccamorgan10. She is represented by Asya Geisberg gallery.

Keith Schweitzer is a New York City based arts organizer, curator and producer. He is Co-Founder/Director of The Lodge Gallery, located on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He is also Director of Public Art for Fourth Arts Block, the nonprofit leadership organization for Manhattan’s officially designated Cultural District in the East Village. You can find him on Twitter as @Keith5chweitzer, and on Instagram as @pseudohaiku.

Wonderful interview. Love her work.